Meteoroids release water vapor into space when they hit the moon – could it have water under its surface?

11/22/2019 / By Edsel Cook

A new study suggests that small amounts of water might hide just beneath the surface of the moon. The lunar water only emerged after a meteoroid slammed deep enough into the lunar rock to extract it.

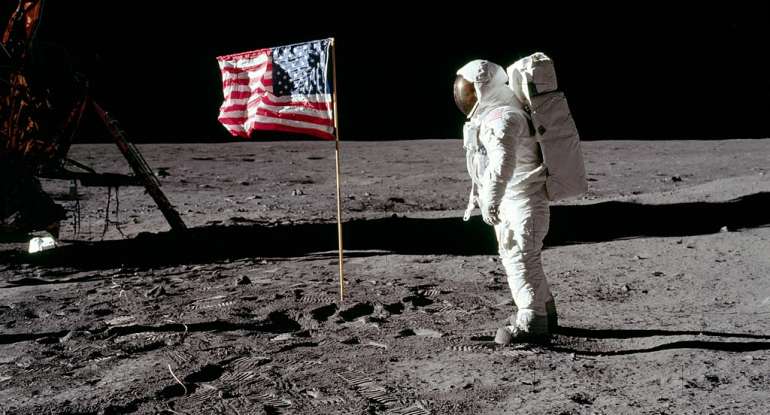

The Apollo astronauts brought back samples of lunar rocks from 1969 to 1972. Analyses found no trace of water in the samples, leading experts to believe that the moon was a dry husk.

However, various orbiters dispatched to Earth’s natural satellite during the last decade detected small concentrations of water on the lunar surface. Further, these same spacecraft detected the life-supporting compound across the face of the moon. Their discoveries dispelled previous theories that only the polar regions might have a shot at holding any water.

Researchers remained interested in the origin of lunar water and its distribution across the moon. They turned to the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE), which circled the moon from 2013 to 2014. (Related: Are people really considering going to the moon… to mine?)

Lunar water may be hiding mere meters beneath the surface

Evaluation of LADEE data revealed that many puffs of water vapor appeared on the lunar surface during an eight-month time span. The expelled water reached into the moon’s exosphere.

Dozens of known meteoroid streams happened to pass by around that time. The Leonids, Geminids, and Quadrantids streams created spectacular night skies on Earth — and they might have played a part in the outburst of water vapor on the moon.

Given the coincidental timing, the researchers theorized that meteoroid impacts triggered the puffs of water vapor on the moon. Furthermore, they attributed four individual incidents to meteoroid streams that escaped observation.

“Most of the geological processes we deal with in planetary science are very slow — we almost never get to see something respond dynamically over the scale of hours like we did here,” explained NASA researcher Mehdi Benna, the lead author of the study. “One would think we know all of the meteoroid streams that are out there, but apparently we don’t.”

Benna’s team evaluated the amount of lunar water that got excavated by meteoroid impacts of different sizes. They noted that the lighter meteoroids produced smaller puffs of water.

Small meteoroids did not dig deep holes. The researchers theorized that the first 3.15 inches (eight centimeters) of lunar soil was dry.

The water in the Apollo moon rocks didn’t make it to Earth

Past that dehydrated layer, water made up 0.05 percent of the weight of the rock that extended downward by at least 10 feet (three meters).

“With our measurements, we could see exactly the water extracted from the moon in a very dynamic way by micrometeroid impacts, and by analyzing the data, see how much water was stored in the lunar reservoir and where it was going,” explained Benna.

He and his colleagues also calculated the amount of water lost by the moon to meteoroid impacts every year. The annual water loss added up to 220 tons (200 metric tons).

Using the dehydration of the upper layer of lunar rock as a measuring stick for water loss over the eons, the NASA researchers came up with two possible origins for lunar water.

In the first theory, the water might have formed alongside the moon billions of years ago. The second theory suggests that lunar water came from asteroids and meteoroids that slammed into the newly formed satellite.

As for the dehydrated lunar rocks obtained by the Apollo astronauts, Benna suggested that the samples didn’t have water chemically bound to them. Any water present might have taken the fragile form of a coating that evaporated during the return trip.

Get the latest news and research on exploring the moon for signs of water (or life) at Space.news.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: asteroids, lunar meteorites, lunar rocks, lunar water, meteorites, meteoroids, Moon, NASA, Space, space exploration, space research, water, water vapor

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 RESEARCH NEWS